What the mountains taught me about leadership

I’ve learned as much about leadership from mountaineering as I ever did commanding people on operations in Afghanistan.

I was asked to lead the British Services Expedition to Makalu, the world’s fifth highest mountain at 8,463m, to take place in 2008. It was one of the most complex leadership challenges I’ve ever faced and the parallels with leading in business are striking.

Vision first, structure second

At the outset I had to create a vision that would draw people in and make them want to be part of something bigger than themselves. We set four ambitious objectives:

A summit attempt via the North side

An attempt on the notoriously difficult Southeast Ridge

A development team on demanding 6,000m peaks

A junior team of novices trekking to base camp and climbing Mera Peak

It quickly became clear I couldn’t lead everything personally. I appointed team leaders for three strands and I led the team on the North side, while retaining overall expedition command. I gave the leaders intent and outcomes but then stepped back and let them get on with it.

The hardest part? Resisting the urge to interfere.

Empowerment isn’t a slogan

Each leader selected and trained their own teams, planned their own approach and owned their risks. My role was to stay close enough to support, but far enough away to let them lead.

Every strand also had a deputy. That decision would later prove critical.

Behind the scenes, I appointed people to run finance, logistics, food, equipment and training. This was not taxpayer funded and we, pretty much, had to raise every penny while holding down full-time jobs. Preparation took three years, mostly at weekends, with a single precious fortnight in the Alps.

Leadership at range

On the mountain, the teams were spread across remote valleys and peaks with (at best) unreliable satellite comms. Trust wasn’t optional it was survival.

Unlike Afghanistan, there was no helicopter on standby. Base camp sat at 5,500m, too high for any rescue aircraft and every decision carried real consequence.

When an early weather window appeared, I authorised our best-acclimatised climber and an experienced Sherpa to make a summit bid. It was a calculated risk. On 4 May a crackled radio message confirmed they’d made the first ascent of Makalu that year. Then, silence! Three sleepless nights followed before they were finally seen descending.

Knowing when to stop

A few weeks later, on my own attempt, I turned around only a few hundred metres from the top as extreme weather set in and I later discovered I had third-degree frostbite.

That decision to turn round hurt but it was the right call.

Because we’d invested in deputies at the outset, leadership continued seamlessly while I was evacuated to try and save my toes. Succession planning in its purest form.

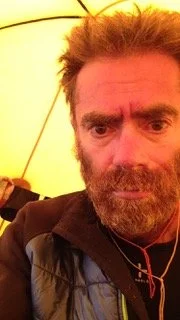

The photograph was taken after descending from a night at 7500 metres on Dhaulagiri without a sleeping bag. I learned a thing or two about personal resilience that night!

What the mountains taught me about leadership

Intent beats instruction - clarity of outcome matters more than detailed control

Empowered deputies are essential - not optional extras

Trust is built long before the crisis

Risk is real - but so is paralysis

Self-leadership really matters - if you can’t manage yourself, you can’t manage others

There is no better classroom for leadership than a challenging outdoor environment. Pressure strips away ego, exposes communication, and reveals how we really make decisions. Time outdoors also makes us think differently and opens up new possibilities.

Its for all these reasons that I am such a passionate advocate of the outdoors as medium for growth!

The photograph was taken after descending from a night at 7500 metres on Dhaulagiri without a sleeping bag. I learned a thing or two about personal resilience that night!